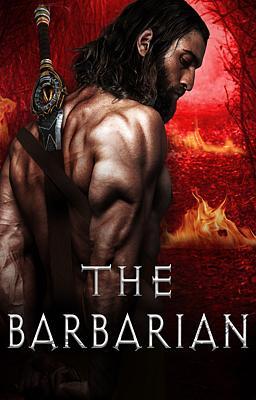

The Barbarian

Author

G. M. Marks

Reads

1.9M

Chapters

27

When Mock the Merciless leads his barbarian horde, destroying village after village, no one is spared. So when he kidnaps Grinda, she knows her fate. But against all odds, love develops between them. Can their love survive amid the hate and fear that divides their lands and their peoples?

Age Rating: 18+

Chapter 1

“So, what do you think?”

Mock pulled up at Croki’s side. Shading his face against the glare, he studied the little village and spat. “Easy pickings.”

His mount shifted uneasily, stomping and gnawing at his bit.

Mock yanked at the reins until he settled. A big draft horse, he was over sixteen hands high with ankles as thick as branches and rippling with ropy muscle. He had once belonged to a farmer.

Mock smiled, remembering the attack fondly. He had spent hours sharpening his sword the night before, and the man’s belly had opened like warm butter beneath his strike.

Even now, Mock could hear his screams as he left him to die. The farm should still be thick with crows. The man had been a father to six, and none had known mercy.

A good day.

The horse didn’t ride fast—he was more used to pulling carts and tilling fields—but he was as black as a witch’s heart, unfazed by blood and screaming, and as strong as an ox.

Fitting for Mock, leader of the barbarian horde, purveyor of death and destruction, murderer, fiend, and rapist of women.

All who saw him quivered and pissed themselves, then begged for their lives—and lost them.

Mock sneered at the little village. It was a fine day for a raid. “Prepare our brothers. We attack within the hour.”

Croki nodded and galloped back the way they had come. The eastern regions had seen peace for much too long. Mock’s hand itched for his sword.

He would soon fix that.

***

“Go fetch more water from the well; we’re running low.”

“Yes, Mother.”

“And did you milk the cow yesterday? She was noisy last night, and Husband says she’s leaking everywhere.”

“No, Mother. But I can do it now.”

“And when you’ve done that, bake some bread. The men will be hungry when they get home.”

“Of course, Mother.”

Grinda’s mother looked down at little Edwin suckling at her breast, her dark hair falling across her face. It was gloomy inside their little one-room hut.

Though the light from the rising sun trailed inside their door and through the gaps in the straw ceiling, it wasn’t enough to alleviate the darkness.

From outside came the sounds of Grinda’s two little brothers playing catch, shrieking and laughing as they chased each other around the house.

They were supposed to be gathering food for the evening meal. The cabbage and onions and some of the potatoes would be ready for picking.

Grinda turned on her heel with a sigh, knowing she would be the one taking on the job. Such an important task couldn’t be left to two gormless boys.

Her shoes whispered through the rushes as she ducked under the door and stepped outside.

“Billy, Jacob, do as Mother says!” she called as she circled the house. They tackled each other to the ground, rolling in the dirt, punching and kicking.

Grinda grimaced. More clothes to wash, more cuts to nurse, more rips to patch.

Billy leapt to his feet with a snort and fled, Jacob close at his heels, both ignoring her as they disappeared around the neighbor’s house.

Grinda bypassed the garden, scattering chickens as she went. The family cow lifted her head at her approach and gave a great bellow, pulling at the rope tying her to the back of the house.

Grinda frowned.

Her udder was painfully swollen, her teats red, and the earth below was wet with congealed milk. She could smell its sourness in the air.

Grinda had heard her all night mooing and stomping but had been too tired to do anything about it.

“I’m sorry, girl,” Grinda said with a rush of guilt, patting her on the neck. The cow shook her head, swished her tail, and gave another bellow. “I just didn’t get the time yesterday.”

She picked up the pail and knelt beside her, lifting her skirts as she did so she wouldn’t get them muddied.

Her teats were wet and slippery, and the milk jetted forcefully into the pail, hitting the bottom with a loud patter. Before long, the pail was almost full, and the cow settled.

Grinda patted the cow’s leg. “Better?”

The cow nosed her hand.

Grinda left the milk for her mother to tend to, fetched the yoke, and headed for the well.

The village was a bustle of activity. Grinda waved at a couple of women as they hauled along their pails of grain and water.

A clutch of little girls whispered and giggled, their baskets filled with fresh eggs and newly picked vegetables.

Grinda dodged a group of young boys throwing sticks and stones and manure at each other. A couple broke off to chase down a barking dog, shouting and whooping.

There were few men, most out on the farms.

Grinda pulled her wimple down over her face as the sun beat on her head. Warm sweat trickled down the back of her neck.

She shifted the yoke, settling it into a more comfortable position across her shoulders, the two pails dangling emptily on either side.

She wrinkled her nose as she passed a woman shoveling manure into a wagon.

The closer Grinda approached the well, the nearer she drew to the smithy, and the louder the sound of banging became.

There was a hiss of steam as the blacksmith dipped the glowing iron into a barrel of water. Sweat poured down his red face and into his thick, bushy beard.

More sweat trickled along his biceps and down his powerful chest. Grinda stared as she passed.

A group of women waited at the well, all sweltering in the heat. Grinda greeted them.

They waved and smiled and said hello, but they were strangely stiff and quiet, as though they’d been discussing something secret.

Grinda frowned, looking curiously between them before setting down her yoke with a grunt of relief.

Even with the pails empty, it hurt her shoulders, rubbing against the old bruises that never had a chance to heal.

“Something wrong?”

Mirabelle shook her head. Agnus looked away. Janelle sighed. Bella had her back to them all, busy at the pulley as she hauled up a bucket of water.

Eva folded her fat arms. “We should probably tell her.”

Mirabelle’s eyes were bright behind her heavy lashes. “I suppose. She’s going to find out anyway.”

“But she’s just a child. We’ll scare her. And what about Karin?” A bead of sweat trickled down Janelle’s cheek. She flicked it away.

Grinda pushed back her shoulders until she stood to her fullest height, which wasn’t much. “I’m not a child, and Mother’s not the boss of me.”

It was a half-truth. Father was the boss, but he wouldn’t care what gossip she listened to as long as she finished her work.

There was a splash as Bella emptied the bucket into her pails.

Eva shrugged. “If you insist. A rider arrived at the village late last night. I didn’t see myself, but I was told he was one of Lord Triston’s knights.”

Grinda’s eyes widened. “A knight? A real knight?” She’d never seen a knight before.

Lord Rickard had once been one, but he was years past his fighting days now—too much pork in his belly, as bald as a trout, and as slow as a three-legged ox.

“Is he still here?”

“Unlikely. I’m sure he would have left at first light to rush to Redburn.” Redburn was the next village over, only an hour away from her village of Quay by donkey trot.

“Why?”

“Well, that’s the news, isn’t it?” Eva glanced at Bella as she came close to listen. She’d left her yoke at the well, and the wet hem of her skirt stuck to her skinny legs.

“It seems we might be in danger.” Eva paused, savoring Grinda’s unease. “It seems there have been barbarian raids on the villages of Quinton and Tacturn.”

The breath caught in Grinda’s throat. Agnus rested a hand on her pregnant belly. Bella frowned.

“But they’re only two days away!” Grinda said. “Do you think they’re going to come here?”

“We’re not sure.” Janelle gave Eva an annoyed look.

“But the knight was worried,” Eva continued, ignoring Janelle. “At least from what I hear. He spoke to Lord Rickard last night.”

Grinda clutched at her skirts. “What should we do?”

“Pray.”

***

Grinda laid out the dishes for dinner, then ladled out the stew. Next, she cut and buttered the bread before pouring them each a cup of water, the same she’d hauled from the well earlier that day.

Her father and three older brothers were tired and dirty and didn’t look at her, much less thank her, as they shoveled food into their mouths.

The day was still bright, the heat gouging at the mud-brick walls of the little hut as the sun settled against the horizon.

A waste to light a candle; the family would be in bed by the time darkness fell.

Making sure Jacob and Billy were settled, she sat among them, feeling the same ache she saw in the lines on her father’s face, the same heavy droop in her brothers’ shoulders.

Her stomach growled, but all she could do was absently push around her food with her spoon. How could she eat when so much hung in the balance?

Her mother sat opposite, trying to eat as Edwin suckled at her breast. The boy was always hungry. He would soon learn not to be.

Their little hut was bare and small, but at least it was cooler than outside.

The doorway faced south, the window north, so they suffered neither the glaring brightness of the morning nor the suffocating heat of the afternoon.

It made for a bearable summer but a freezing winter.

The roof was made of mud and straw, baked hard, and the floor was much the same: beaten earth covered in a dusting of rushes, which Grinda shoveled up and replaced when they got too dirty.

Her father scraped the bottom of his bowl with his spoon and looked up. He glanced at her dish. “You’re not eating, daughter?”

“No, Father.”

“Are you sick?”

She shook her head.

Her father rested back against the wall, his hands on his firm belly. His fingernails were black with grime, and there were streaks of mud and blood on his thick forearms.

He was looking haggard and old, more gray in his beard than brown, the lines running deep in his furrowed brow and at the drooping corners of his mouth.

His tunic sat loosely on his shoulders. His pants were belted with rope. Life was hard and harder still with so many mouths to feed.

“Then share it among your brothers,” he told her. “Lord knows they need it.”

She pushed over her dish, and her brothers crowded around it, digging in their spoons. Grinda watched her father carefully, but he showed no sign of anxiety. Surely, he must have heard the news.

She cleared her throat. “Father?” He raised his eyebrows. “Did you—did you hear?”

He pressed his lips together. “Yes, I heard.”

Grinda glanced at her mother. She lowered her face over Edwin, her long, dark hair concealing her expression, but Grinda could see the tension in her shoulders.

“What must we do?”

“Nothing.”

Grinda hesitated. To question Father was like poking a stick at an angry boar, but even her fear of his formidable wrath was no match for the thought of a horde of bloodthirsty barbarians.

Torture, murder, rape. Grinda clenched her knees together. She’d heard the tales.

“Is that—is that wise?”

It was as though a heavy shroud fell over the hut. Everyone froze. Silence fell. Even Edwin stopped fidgeting.

The walls closed in, and she lowered her eyes to the table, the heat of her father’s glare burning against her cheek.

“You dare question me, daughter?”

Grinda hunched over, tucking her chin to her chest. Her arse clenched as she recalled the sting of his lash. She was still raw from the last time. “I’m sorry, Father.”

More silence. Grinda didn’t move. Then came Father’s deep sigh and the rasp of fabric against brick as he relaxed against the wall again.

The shroud lifted. Her brothers went back to their stew. Edwin mewled and sucked. And Grinda dared look up.

“There is no sin in knowing fear, especially for a woman,” he said.

“But the situation is under control. Word has it Lord Triston has sent three companies of his finest men to meet the barbarians head-on. They won’t know a second dawn.”

Grinda nodded. “Good, Father.”

Edwin whined as Mother shifted him to her other breast. The bench wobbled as Billy and Jacob began kicking each other under the table.

Spoons scraped against an empty dish. And Grinda gazed through the window, digging her fingers into her knees until it hurt.